- Home

- Anna Carey

This Is Not the Jess Show Page 2

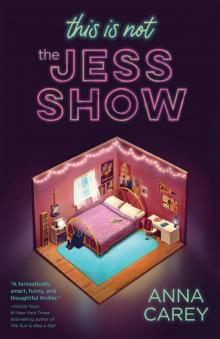

This Is Not the Jess Show Read online

Page 2

“My mom had a work emergency. She never got off the phone.”

“Oh.” Tyler shrugged. We usually IMed at least Friday or Saturday night, just blabbering on about stupid stuff, like Mr. Betts’s new toupee.

I thought he might say something else, but he just drummed on the side of the storage shelf, tapping out a quick rhythm. His cheeks were turning this splotchy pink color. They only did that when he was nervous.

“What’s wrong?”

“Nothing, no.” He shrugged.

“Ty, say it.”

“I guess I just missed you?”

It was a question. He looked up and gave me this half smile, then started laughing. “Fine, I said it. I missed you, whatever. You’re my everything, Jess Flynn, it’s torture without you, blah blah blah. You happy now?”

“Extremely,” I said, and I felt the fire in my cheeks, all the blood rushing to my face at once. “I have that effect on people…”

He turned and grabbed the snare drum, carrying it in front of him as he walked out. He stopped right beside me, leaning in so his lips were just a few inches from my ear, and I could feel his breath on my neck. His freckles always disappeared during the winter, but when we were really close I could see the faint remnants of them along the bridge of his nose.

“You definitely have that effect on me.”

Only this time, when he said it, he didn’t laugh or make it a joke. His hazel eyes met mine and there was a moment when I was sure he would kiss me, right there, in the storage closet. Every inch of my body was suddenly awake waiting for him.

But then he turned and walked to the back of the room. He looked back twice, smiling at me over his shoulder. Something had changed. He wasn’t the same person who’d slept next to me that night in the treehouse, when we were eleven, scanning the trees with a flashlight, looking for bears (even though we both knew Swickley didn’t have any). The air between us was charged, and I noticed every time he brushed my shoulder or the back of my hand.

I set up the keyboard stand behind the clarinet section, feeling Tyler’s eyes on me the whole time. When I looked up his cheeks were still pink and splotchy. I kept running through the conversation. It was like I’d been possessed by someone older and more confident. I have that effect on people.

The sub pulled her gray hair back with a checkered scrunchie, then tapped the conductor’s baton against her music stand. A French horn player stopped halfway through her scale. The class was still only about half full.

“I’m Mrs. Kowalsky, your sub for the next few days. I know we don’t have a full band, and we’re missing almost all of the saxophones…” She glanced at Ajay Sethi, who looked particularly lonely surrounded by empty chairs. “But let’s do our best. Starting from the top.”

She rapped the baton against the stand again, then brought it up in front of her face.

Even after the first song began, the trumpets blaring the first notes of the Friends theme, our eyes kept finding each other. The whole period I was thinking of Tyler’s mouth, how red his lips got when he blushed. I kept wondering what it would be like to kiss him.

3

“We can’t risk Sara getting sick.” Lydia pushed a heaping pile of salad onto her plate. “I think I’ve sprayed every inch of this house with Lysol.”

Sara pushed her mashed potatoes around with her fork. She was still in her pajamas, even though it was after six o’clock. My dad always carried her downstairs for dinner, singing “Here she comes, Miss America…” the whole way.

“That seems kind of unlikely,” Sara said, “considering I see the same four people every day.”

“I had to move all the Reyes’s new furniture into storage,” my mom went on. “The new dining set, every lamp and table I bought for the living room. We were supposed to be putting the finishing touches on tomorrow, but Vicki’s sick, and I wasn’t about to risk it. We won’t be done for another two weeks. That’s if we’re lucky.”

My mom was one of Swickley’s most popular interior designers. Her business grew organically after she renovated our house. She’d spent a whole year huddled over fabric swatches and paint chips, a measuring tape glued to her hand. She was the one who’d chosen the gray Formica dining table we were eating at. She’d paired it with these asymmetrical chairs that look like someone hacked them in half with a machete. Our living room was painted pale turquoise, but even with the fuchsia carpeting and black media cabinet, it somehow all worked. When she insisted on pink walls in the kitchen we fought back with everything we had. I suggested five other options; Sara said it would feel like swimming in a bottle of Pepto-Bismol. It wasn’t until Amber and Kristen came to see it after school that I realized it wasn’t as horrible as we’d thought. Maybe it was even kind of…cool?

“I’m just hoping I don’t lose too much time,” my mom went on. “The kitchen renovation on Oakcrest is a complete disaster. There’s only one guy left on the crew. Everyone else called in sick. It took him six hours just to install the sink. I can’t even imagine what I’m going to have to deal with tomorrow.”

“Sounds rough,” I said. She was getting into that hyperfocused place where all she could do was talk about work. I turned to my dad, hoping he’d derail her, but he was cutting his steak with the precision of a neurosurgeon. He held up a tender piece, studying it on his fork before taking a bite.

In the past few years my dad’s conversational skills had shrunk to short phrases, as if it took too much effort to form any kind of imaginative or complicated thought. My mom addressed it without addressing it, saying that he was “under a lot of stress” and “having a hard time with Sara’s illness” or, my favorite, that he was “a man of few words.” It was a horrible masculine cliché, but the only time he seemed genuinely excited about anything was when he talked about the Swickley High varsity baseball team. He’d been the head coach since I was a kid. I’d formed all these theories about sports being a socially acceptable way for men to talk about their feelings, to scream and cry and rage against the world. I was certain that when he teared up after the team lost the championships last fall, it was really about losing control, and how he felt about everything our family was going through.

Mostly, though, I just missed him.

“Oh, I should show you the design for the Hill Lane project,” my mom barreled on. She looked from me to Sara, but I couldn’t figure out who she was talking to. “You’d love the master bedroom. All florals. Simple. I usually resist florals because it feels grandma-ish, but what Betsy Baker wants, Betsy Baker gets. That woman is a force.”

The table was quiet and for a second I thought I heard it again, that same chanting from the other morning. It was hard to be sure because the stereo in the kitchen was still on. The radio station played a Dave Matthews song I hadn’t heard before. Something about not drinking the water.

“Forages…” I stared down at my plate, to the last grisly bits of meat. “That just means to look for food, right? It’s not like there’s some other obscure definition?”

My mom tilted her head and studied me. “Where’d that come from?”

“I just…” I started. “I heard it the other morning. It sounded like it was coming from outside, like someone yelling. Forages, power. Forages, power. Over and over like that. But then I couldn’t hear it anymore.”

“That’s what you were asking about yesterday?” Sara said.

“And for a minute or two today, right when I got up.”

Sara turned to Lydia. Her dark brows knitted together the way they did when she was pissed. Lydia stared straight ahead. It was like she was purposely ignoring her.

“What?” I asked. “What’s wrong?”

“Very strange…” My mom said it in this chipper, high-pitched voice. “Does anyone want more steak? There’s two more pieces.”

“I’m good,” I said.

It wasn’t the type of conversat

ion my mom was interested in. She would’ve been happier if I’d engaged with her on her Oakcrest kitchen design, or if I’d told some funny, meaningful story about school. The thing about having a mom who obsessed over the tiniest aesthetic details of our house was that her obsession extended to all the people in it. She was always suggesting new hairstyles (you should grow out your bangs, shorter cuts are harder to pull off), and one time she’d bought me a whole pile of new clothes without asking. She’d paired different skirts and sweaters together and had all the blouses tailored to my frame. Everything I said and did and wore had to be just right.

I stacked Sara’s and Lydia’s plates and started into the kitchen. Sara was glancing sideways at Lydia again, like she might say something else, but she didn’t. I wondered if she’d heard the words too, or if she was just responding to my mom’s obsessive need to control the conversation. I’d have to ask her when we were alone.

Sometimes just being in a ten-foot radius of my mother was enough to make me feel anxious. When I was thirteen I begged her to let me take guitar lessons, though she went on and on about how I was such a beautiful piano player—why did I want to change instruments? Sam, she said to my dad. Tell her what a waste that would be. It had taken months to wear her down, but she finally agreed that if I kept playing the piano I could also take guitar. I’d do both.

But six lessons in my guitar teacher, Harry, had what my parents described as a “psychotic break.” He’d been showing me how to play “Landslide” when he paused, staring at the mirror that hung across from our sofa. He asked if I’d ever wondered about the nature of reality. Did I ever feel, in my gut, that there was more to this world? That things were oppressively surface level? Did I ever feel trapped in someone else’s delusion?

I wasn’t used to people asking my opinion, so I had to really think about it. Sometimes things feel weird…like I don’t have control, I said. Like I’m trapped. Is that what you mean? I started to tell him about my mom, and how she needed to know where I was every second of every day, but then my dad walked in. He’d heard the whole conversation from the kitchen.

Harry never came back to our house. When we went to Mel’s Music a week later, they said he’d moved in with his mother in New Jersey. He’d been hearing things, an egg-shaped man behind the counter said. His gray beard was so long it made him look like Rip Van Winkle. He wasn’t well…in the head, you know?

I rinsed the dishes and went downstairs. I looked at my reflection in the mirror above our sofa, trying to see what Harry saw in it. Maybe I was smart enough not to say it out loud, but I still did question “the nature of reality.” I did feel like everything was surface level. And now I was hearing things, too.

He wasn’t well…in the head, you know?

I was starting to feel like I did.

4

Kristen pulled on her jeans, never taking her eyes off me. She was always the slowest to change after gym class, lingering in her bra, her flannel shirt balled in her hand, or using those seven minutes before the bell to launch into some in-depth conversation that would inevitably spill into the hall. I couldn’t help but wonder if it was because her boobs were three times the size of mine and Amber’s.

“You’re being so annoying,” I said. “Come on. Out with it.”

Kristen peered around the corner of the gym lockers, checking the shower to make sure no one was there. The tiled room was only used for storage, but sometimes girls sat on the stacked gymnastics mats and smoked out the window.

“Fine…Patrick Kramer is going to ask you to Spring Formal.” Kristen drew out the sentence, pausing after each word.

“She heard it from Patrick’s best friend,” Amber said, clipping her overalls in front. “It’s like he wanted it to get back to you.”

“Patrick Kramer,” I repeated. It wasn’t enough that he was six foot three and started on the varsity soccer team. Last February he’d been at the Empire State Building when a guy opened fire on the observation deck, and he’d jumped in front of a group of third graders, bringing them all to the ground. No one was hurt. He’d given interviews to STV News. He’d been in every paper, with headlines like “Young Hero Saves Third Grade Class” and “Bravery at the Empire State Building.” I might’ve liked him based on that alone, but it was more than a year later and he was still trying to work it into every conversation, as if everyone hadn’t already discussed it ad nauseam.

“Patrick and I are complete opposites. And we’ve only ever talked like, a handful of times. Mostly about Physics homework.”

“You don’t need to talk to enjoy his abs.” Kristen turned and folded her arms around her body, making sucking noises as she ran her hands up and down her sides. We laughed, but that wasn’t enough for her, and she kept going, grabbing her own butt until I nudged her to stop.

“It just feels out of nowhere.”

“Apparently he’s liked you since Homecoming. And I double-checked to make sure he wasn’t talking about Jess Aberdeen, Jess Thompson, or Jess Weinberg.” Kristen finally pulled on her baby doll tee, then plopped down on the bench to lace up her Doc Martens. She didn’t take anything too seriously—crushes, homework, even the SATs. With Sara sick, I wouldn’t leave Swickley after graduation—I couldn’t. The only thing that made me feel better was the idea that Kristen might be here with me.

“He’s just not my type. Besides, things are finally happening with Ty.”

“If things were going to happen with Ty, they would’ve happened already.” Amber pointed her lip gloss wand at me. “Seriously, Jess, you’ve known him since fourth grade.”

“It’s not easy to go from friends to something more,” I said. Ty wasn’t a Patrick Kramer, one of these guys who tried to shove their tongue down your throat as soon as they got you alone. “He’s probably only just realized I like him.”

“I mean, I knew as soon as he left my house that day.” Amber raised one eyebrow. With a swipe of berry lip gloss she looked flawless—not like she’d spent the last forty minutes playing a vicious game of badminton.

“Well, he wants to ask you this Friday,” Kristen said. “Jen Klein’s having people over.”

“Friday? Two days from now?”

It felt too soon to have to make a decision. Saying yes to Patrick meant saying no to Ty, even if he hadn’t officially asked me anything yet. I couldn’t do that. I didn’t want to.

“He’s hoping you’ll come…” Amber said. “And, to be honest, we are too. It’s been like, a hundred years since you hung out on a weekend.”

I’d been to those parties before. Weaving through the crush of sweaty, flailing bodies. Cigarette smoke and people spilling shit on you and feeling awkward because I was never wearing the right thing. I’d always admired how Amber could walk into a room and make anyone her friend, how she wasn’t preoccupied by what people thought of her. Whenever someone complimented me I doubted it was genuine, and lately everywhere I went I felt skinless—overexposed.

“Come on, Millie loves parties,” Kristen said, threading her arm through mine. Millie was Kristen’s 1990 Volvo station wagon. She was pee-yellow, with ripped leather seats, but she was our portal to freedom.

“So are you in or what?” Amber finally asked, pulling on her backpack. “We’ll get dressed up, arrive fashionably late. Make a big entrance. Maybe I’ll steal some wine coolers from our basement fridge.”

Even if I didn’t like Patrick Kramer, and I didn’t want to go to Spring Formal with him, there were other perfectly good reasons to go to Jen Klein’s party. Tyler lived three houses down from her. It wouldn’t take much for him to stop by, even for just a little bit.

“Hmmm…” I smirked. “What time do you wanna pick me up?”

“That’s the Jess I know and love.” Amber wrapped her arms around me and planted a sticky kiss on my cheek.

“We’re going to a partaaaaaaay,” Kristen said as we started out of the lo

cker room. She did a spin, then a slide, but it all looked more Elaine-from-Seinfeld than Britney Spears.

Amber grabbed my hand and we both dipped down to one side, then back up. We’d been in dance class together when we were kids, and we still sometimes did bits of our old routines. She hopped forward, leading me, when something fell out of the bottom of her backpack. It skidded across the tile and under one of the wood benches.

“I got it,” I said, kneeling.

The flat silver cartridge was just smaller than my hand, with shiny black glass on one side and metal on the other. I turned it over and pressed a button. Nothing happened.

“What’s this?” I glanced up at Amber.

Suddenly it blinked on, and I caught a glimpse of something behind the glass. But then Amber grabbed the cartridge out of my hands and started fiddling with her backpack, where a mesh pocket had come undone.

She didn’t respond until it was tucked away and everything was zipped shut. “What?” she said.

I stared at her. “That thing that fell out of your bag.”

She adjusted the knapsack so it was in front of her, her arms wrapped around it like a fake belly. She was already a few steps ahead of me when she finally spoke.

“It’s just…” Her words were slow and deliberate. “I found it in my dad’s briefcase. I was going to ask Mr. Henriquez if he knows what it is.”

“Mr. Henriquez? The Tech teacher?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Amber shrugged. “It’s just weird. My dad’s had that job forever, and he barely says anything about it. I’ve never seen his office. He’s never home for dinner. Then I find this.”

I glanced sideways at Kristen, but she was staring at the floor. It seemed like they’d already discussed the weird contraption, whatever it was, but neither of them wanted to tell me anything. What did Amber think Mr. Henriquez was going to say? And what was she implying, exactly? That her dad was a spy? That he was having an affair?

The Real Rebecca

The Real Rebecca Once

Once Rebecca Rocks

Rebecca Rocks Blackbird

Blackbird Rise

Rise Rebecca's Rules

Rebecca's Rules Deadfall

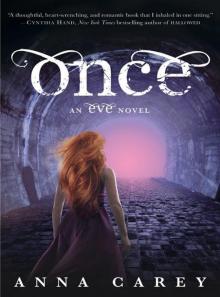

Deadfall Eve

Eve The Making of Mollie

The Making of Mollie Sloane Sisters

Sloane Sisters Survival of the Fiercest

Survival of the Fiercest This Is Not the Jess Show

This Is Not the Jess Show Once: An Eve Novel

Once: An Eve Novel