- Home

- Anna Carey

The Boldness of Betty Page 2

The Boldness of Betty Read online

Page 2

I hadn’t planned on saying anything at all, but when he said that I found the words exploding out of me. ‘It’s not fair,’ I said. Well, I say said, but it was more like a yell. ‘It’s just not fair! I’m good at school. You know I am! It’s stupid that I have to leave.’

‘Life isn’t fair, pet,’ said Da, which is the sort of irritating thing parents say whenever you complain about everything, but he sounded as if he really meant it this time.

‘I could have got a scholarship,’ I said fiercely. ‘Somehow. And then I could go to Eccles Street or Loreto on George’s Street, or one of them places. You know I could have.’

I don’t even know if those fancy schools give scholarships, but no one had even tried to check for me and I had no way of checking myself.

‘And you know that we need a wage coming in,’ said Da gently. ‘We can’t afford to have anyone not working who could be working. Things are rough in this city these days. For all I know, they might sack all of us dockers tomorrow.’

I know this is true. And I know I have to do my bit for the family. All the girls and boys around here do. But it doesn’t stop me wishing I didn’t have to, and I couldn’t pretend I didn’t mind.

‘If I stayed in school, I might earn more money in the end,’ I said. ‘I might even be a teacher, or something. They must earn more than I’ll earn in that cake shop place.’

Da sighed. ‘Look it, if you work for a while and save up a bit of your wages, you’ll have enough money for one of them typewriting classes. You could get yourself a fancy auld job in an office.’

I didn’t say anything.

‘And it’s not as though you’ll be going into service,’ said Da, forcing some cheerfulness into his voice. ‘We won’t be sending you out to scrub floors. You’ll work in that shop for a while and then once you’ve learned to use those typing machines you’ll go and work in a nice warm office wearing a silk frock and typing out some rich fella’s letters. That doesn’t sound too shabby, does it?’

He was being so kind I couldn’t stay angry with him. When he put his arm around me I gave him a big hug back, and then I went back into the kitchen where Ma had a slice of cake ready for me as a leaving-school-treat. She gave me a hug too, and she was very nice to me for the rest of the evening. But I knew they didn’t understand, not really. I wanted to stay at school so I could learn things, even the boring things like geography, because then maybe I could go to college and read lots of books about things I am interested in. And maybe after that I could become a teacher or, I don’t know, anything at all. Even a writer. Something other than being a servant or working in a shop or a factory like most girls around here.

Because here’s one thing I haven’t ever told anyone else, not even Samira: what I want most of all is to write stories, and in fact the main reason I’ve started writing this memoir is to practise writing something. And if I’m being perfectly honest, I don’t see why I couldn’t write a book when I grow up. I mean, lots of people write books, so why shouldn’t I? Charles Dickens was sent out to work in a factory when he was even younger than I am, and he went on to become one of the most famous writers ever. And when I become a famous writer I’m sure people would find it very interesting to read about my early years.

But I’d never say any of this to Ma and Da. Every time I tried talking with them about staying at school we had a big row because they thought I was just being silly. And maybe I am. It’s not like having to leave school was a surprise – I always knew it was going to happen. So I’ve made the decision not to say anything about it again. Anyway, those are my ma and da. They don’t really understand me but they’re all right I suppose.

The last but most important member of the family is the aforementioned (another fancy word!) Earnshaw. Earnshaw is not a person, of course, he is a dog. Da found him on the docks when he was a puppy and took him home because they couldn’t find his mammy, and Lily and I wrapped him in a blanket and fed him out of a bottle until he was old enough to eat scraps.

‘If I’d known what he’d grow into,’ says Ma sometimes, ‘I’d have drowned him in a bucket back then when I had a chance.’ It’s true that he’s a peculiar-looking sort of dog, but I think that makes him more interesting. Sometimes people stare at him in the street, but I’d rather have a dog that people stared at than some boring old terrier who looks like all the other dogs and who no one even notices. Anyway, whatever Ma says about Earnshaw, we all know she loves him really. She even sings songs to him when she thinks no one can hear her. Everyone loves Earnshaw, even Eddie who pretends he doesn’t care about anything.

And that’s our family. In comparison to some people round here there aren’t very many of us, only three kids (and we don’t all live in our house anymore). There are some families with even fewer (that’s good grammar, the nuns would be proud of me). The Phelans only have two kids (though they have two policemen lodgers, Mr Carroll and Mr Ward, who sleep in the front room).

There should have been more children in our family, but Ma had two babies who died. I never saw them. One was called Thomas and he was born two years after Lily. Another was called Mary and she was born a year after Eddie. They only lived for a few weeks each. Most families on our road have had at least one baby who died.

There are still lots of big families though. The O’Hanlons have ten kids, in a house the same size as ours. Lily and Robert Hessian only have one so far, and it’s to be hoped they don’t have any more, if my nephew Little Robbie is anything to go by.

I forgot to mention Little Robbie when I was listing all my relations. That’s because I try to pretend he doesn’t exist. You wouldn’t think a baby could be so terrible but he is. He was born a year ago and when he was tiny he just cried all the time, which lots of babies do, I suppose, so I can’t blame him for that (see how reasonable I am?). But once he got a bit older and started showing some personality, his true nature was revealed.

He’s all smiles to his mammy and daddy and to my ma and da, and he doesn’t seem to care much about Eddie one way or another, but as soon as he gets anywhere near me he turns bright red and starts roaring. Practically the minute he got teeth, he bit me. I told Ma I should go to the doctor because I was worried I’d get poisoned, like when people get bitten by mad dogs, and she told me to go on out of that. No one in our family ever goes to the doctor, I think they’d only get you a doctor around here if they thought you were in danger of dying and probably not even then. They’re just too expensive. Then she said that I wouldn’t get poisoned by a beautiful baby like Little Robbie.

‘He’s not a beautiful baby, Ma,’ I said. ‘He looks like a tomato in a wig.’ Because as well as going bright red whenever he’s angry, which is most of the time, he also has a shock of black hair. He was born with it, and if you ask me he just gets hairier and hairier as the days go by. It doesn’t seem normal for a baby to have so much hair, or such a red angry face. Ma doesn’t agree, of course.

‘He looks nothing like a tomato!’ she said. ‘Actually I think he looks just like you when you were his age. You were a very hairy baby too.’

Me, looking like Little Robbie! I think this might have been the most insulting thing anyone has ever said to me. Anyway, Ma says I have to stop being horrible about him.

‘You can’t say that about your own nephew!’ she says, whenever I give out about him biting me or getting sick on me or head-butting me in the face. ‘He’s a little dote and an angel-love!’ But he really isn’t either of those things. He’s a monster in disguise. And not a very good disguise either.

Right, Ma just got home from the Connollys and started giving out to me for not starting on the potatoes, so even though I haven’t written a word about Samira yet, or the new job I’m starting in a few days, I’m going to stop writing now and hide this notebook under my mattress. I wouldn’t trust Eddie to leave it alone if I left it in the kitchen.

Chapter Two

This time tomorrow I will officially be a working woman. Well, a working gi

rl anyway. I’ve had a few sweet days of freedom, which I spent sitting in the back garden with Samira reading library books and talking about all the things we’d like to do with our lives if I didn’t have to go and work in a cake shop and tearoom and she didn’t have to go to work in the shop at the top of the road. But now, as Eddie has been delighting in telling me, I have to ‘enter the working world’. Whether I like it or not.

The cake shop and tearoom where I’m going to be working is called Lawlor’s, and it’s on Henry Street. I actually got the job because one of Ma’s dressmaking clients is the wife of the owner, Mrs Lawlor herself. Ma is very good at making clothes. Before she married Da she worked in a drapery in town called Whyte’s which is quite grand. Her ma and da, my Nanny and Granda, live in a little cottage near Skerries and when Ma was fifteen she moved down to Dublin to work in the shop. All the shop assistants lived in a sort of lodging house that was part of the shop, so she was on the premises all the time. This doesn’t sound much fun to me but she says it wasn’t too bad.

When Ma worked at Whyte’s, she sewed all her own clothes with the ends of the rolls of fabric they sold in the shop, which she could buy at a discount, and these clothes were so exquisitely made (that’s another good word, exquisitely) that customers who came in there buying cotton or wool materials began asking her about them. She started doing a bit of dressmaking herself in her spare time and earned enough to buy a decent secondhand sewing machine.

Some of those customers were very grand people and Ma had to go to see them at home to show them the clothes and make alterations, so she’s visited big houses all over the city and she knows quite a lot about how fine ladies and gentlemen live. This is why Mrs Hennessy down the road thinks Ma has notions. I suppose Ma sort of does have notions, at least in comparison to Mrs Hennessy.

And she still has the sewing machine. She always says that if you look after a sewing machine it should last you all your life. That’s how she makes clothes for her grand ladies in Drumcondra and Clontarf – like Mrs Lawlor. Mrs Lawlor lives on the Howth Road in Clontarf, in a massive house with coloured glass in the door, and I’m sure she has never gone behind the counter of the shop her husband founded twenty years ago.

I’ve met her, though. In fact, I first met her a few months ago and I suppose that day changed my life, because without it I might not be going to work in Lawlor’s tearoom tomorrow. It was back in March when I went over to her house one day with Ma to fit some frocks for her daughter, Lavinia Lawlor. They were part of Lavinia’s birthday present and Ma needed her to try them on in case any final alterations were needed. At least she knew they weren’t too long – she’d realised when she took the first measurements that me and Lavinia Lawlor are exactly the same height, even though she is about three years older than me, so she’d got me to try them on when she was doing the hems.

Afterwards I almost wished I hadn’t gone to the Lawlors’ house – not that I had a choice in the matter. My assistance was required because Mrs Lawlor had ordered so many frocks that Ma couldn’t have carried them and her sewing bag all the way to the Howth Road on her own. Or at least not without getting them all crumpled up. But I felt peculiar about going. That wasn’t just because the frocks started to feel pretty heavy after about half a mile, but because Lavinia Lawlor goes to school with the Dominican nuns in Eccles Street.

One of my teachers in William Street went to school there before she trained to become a teacher, and she told me that the girls in Eccles Street learn French and German and music, and play tennis and put on plays and get taken to the theatre. And then when they’re finished school, some of them go on to college. Ever since she first told me about this, I’ve dreamed of going to that school. It’s only a mile or so away – I could walk there easily. I used to dream of going there and learning how to speak French and German and read Shakespeare. That was before I had to accept that there was no chance of it ever happening in real life.

But I’m pretty sure – in fact, I know – that all of those advantages have been completely wasted on Lavinia Lawlor. When we arrived at the house in Clontarf on that day back in March, we knocked on the kitchen door underneath the front steps (of course we didn’t go up the steps to the front door). A tall thin woman with a red friendly face answered the door.

‘Ah, Mrs Rafferty,’ she said, with a cheery smile. She had a country accent though I couldn’t tell you where exactly she was from. ‘Good to see you again! It’s been a while, so it has.’

‘I told you, Jessie, call me Margaret,’ said Ma with a smile. ‘Mrs Lawlor asked us to make a few things for Miss Lavinia’s birthday, so I’m here to do the final fitting.’

I didn’t like hearing Ma call Lavinia Lawlor ‘Miss Lavinia’. She doesn’t call Samira Miss Casey, and Lavinia Lawlor is no better than any of my friends. But of course I didn’t say anything about this to Ma.

‘I’d better show you up there myself,’ said Jessie. ‘The other girls are sorting out something for Mrs Lawlor in the attic.’ It took me a while to realise that the ‘other girls’ were other servants, not daughters of the house. We followed Jessie through the lovely warm kitchen (which was about the same size as our entire house, and had big hams hanging from the ceiling. Whole hams, just for one family! I’ve only ever seen a ham in the window of the butcher’s shop) and up the stairs to the hall.

I had never been in a house like this before, and even though I was trying to act as if I were invited to places like this all the time, I couldn’t help looking around me and staring at everything. Because there was so much to stare at. The first thing I noticed was a beautiful little hall table with a gong on it. It was suspended in a wooden frame and resting on the frame was a little mallet. I suppose Jessie (or one of the other servants) hits the gong with the mallet when it’s time for dinner, like they do in books.

At the foot of the stairs was a grandfather clock and the face of it was covered in stars and moons. I wish I had a clock covered in stars and moons. There were paintings on the wall – actual paintings, not just holy pictures or pages cut out of magazines, which is all we have at home. You could see where the brush had left marks on the canvas. The sun shone in through the coloured glass in the door and made a pattern on the tiled floor We don’t have tiles in our house, just lino and some rag rugs.

Jessie opened a door and ushered us into the drawing room, and that was even more beautiful than the hall. It was exactly the way I imagine Pemberly, Mr Darcy’s big house in one of my favourite books, Pride and Prejudice. The walls were papered in yellow and there was a picture rail around the top with lots of beautiful paintings in gold frames hanging off it. There was a carpet on the floor so thick and soft you practically lost your feet in it. A massive piano stood in one corner and on the piano were photographs in silver and leather frames.

On each side of the fireplace was a big sofa, with fluffy cushions, and armchairs that were about the size of the sofa in our front room. Hanging from the ceiling was a chandelier, like they have in the entrance to the picture house. I’ve never seen one in a house before. It sparkled in the sunlight coming in through the massive windows. This was when I stopped trying to look all casual and just openly stared at everything in amazement.

‘I’ll tell Mrs Lawlor you’re here,’ said the friendly Jessie. ‘Miss Lavinia isn’t home from school yet but she’ll be in any minute.’ She bustled out of the room.

Ma smiled at me. ‘Now isn’t this a treat?’ she said. ‘It’s not often you get to visit a house like this, is it?’

‘Can we sit down?’ I said, looking longingly at the big sofa. I wanted to know what it would feel like to lie back in all those cushions. But Ma looked as if I’d asked if I could rip up the cushions with a knife.

‘You certainly can not,’ she said. ‘And you won’t say a thing unless you’re spoken to.’

I thought, well, if visiting a grand house means I have to act like a dummy in a shop window and I can’t even sit down for a rest after walking in the heat, I

’d rather stay in the North Strand. And just as I was thinking this, the door of the drawing room opened again and a woman came in who was so tall and elegant I was instantly sure that me and Ma looked like a pair of drab little mice in comparison, even though I was wearing a cotton frock covered in tiny flowers which is one of my favourites, and Ma always looks lovely and neat and trim.

Mrs Lawlor was wearing a fawn-coloured linen skirt and a cream lace blouse with a beautiful brooch at the neck. On her feet, peeking out from under the linen skirt, were the most elegant fawn kid shoes. I suddenly felt very aware of the scuffs on my nice clean black leather button boots. Ma always tells me I’m lucky to have shoes at all because most of the children in the tenements in town certainly don’t, and I know she’s right, but my boots looked so old and big and clumsy in comparison to Mrs Lawlor’s dainty slippers. I crossed one foot behind the other.

‘Mrs Rafferty,’ she said, and even though her appearance was grand her manner was warm and friendly. ‘How kind of you to come.’

You told her to, I thought, but then I felt bad because Mrs Lawlor was being nice. She spoke as if she really were happy to see Ma. Now she was smiling at me. ‘And who is this?’

‘This is Betty, Mrs Lawlor,’ said Ma. ‘My youngest girl.’

‘How do you do, Betty?’ said Mrs Lawlor, and as I’d actually been spoken to I presumed it was all right to say, ‘Very well, thank you.’

‘Betty helped me carry over the clothes for Miss Lavinia,’ said Ma. ‘And she helped me with the alterations at home.’

‘Well, I’m very glad you did,’ said Mrs Lawlor. ‘Lavinia never seems to have time for things like dress fittings. It’s always the tennis club or some other romp.’

She glanced at the mantelpiece, where there was a lovely little wooden clock with roses painted around it. ‘She should be home by now.’

The Real Rebecca

The Real Rebecca Once

Once Rebecca Rocks

Rebecca Rocks Blackbird

Blackbird Rise

Rise Rebecca's Rules

Rebecca's Rules Deadfall

Deadfall Eve

Eve The Making of Mollie

The Making of Mollie Sloane Sisters

Sloane Sisters Survival of the Fiercest

Survival of the Fiercest This Is Not the Jess Show

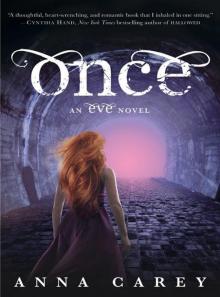

This Is Not the Jess Show Once: An Eve Novel

Once: An Eve Novel