- Home

- Anna Carey

The Making of Mollie Page 3

The Making of Mollie Read online

Page 3

‘Oh don’t worry,’ said Father. ‘I will continue to slave for the government and keep you all in the style to which you’ve clearly become accustomed. Now, who wants to hear Chapter Ten?”

And though, as usual, we all groaned and pretended we didn’t want to hear it at all, we did really, because Father’s story is actually quite good. To be honest, it’s so good that sometimes I wonder if he really COULD earn a decent-sized crust through his pen. It is all about a young man who is falsely accused of stealing some jewels (he says he was inspired by The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins, which is also very good and also about stolen jewels). The young man in Father’s story, whose name is Peter Fitzgerald, has to go on the run and is pursued by both the forces of the law and a gang of jewel thieves who are convinced he has the jewels on his person (which of course he doesn’t, as he never stole them in the first place).

We have now reached a bit in which Peter Fitzgerald is hiding in the cottage of a mysterious old lady. Harry thinks she is going to betray him to the gang ‘because women have no sense of loyalty’ but I totally disagree. Father is not giving anything away. He says we will have to wait and see. But I wonder if he suspects that there is a mystery going on in his very own house with his very own eldest daughter?

19th April, 1912.

Dear Frances,

Thank you for your letter. I am very relieved to find out that the teachers don’t read your post, though Nora said I probably should have checked that before I sent you anything. She said in most schools they actually do read your post, which I am sure is illegal. But Nora said those sort of laws didn’t count at school, which seems terribly unfair to me.

And your lovely teachers are taking you to Stratford, how thrilling! I used to think Shakespeare was awfully boring, but actually this year we have been reading Romeo and Juliet and he’s not bad, really. As You Like It is meant to be jolly good so I’m sure seeing it in Shakespeare’s native land (so to speak) will inspire you when you’re putting on your own drama club play. I agree that you should write your own play but don’t be discouraged if your classmates want to do something tried and tested (i.e. old) instead. Genius, as Professor Shields sometimes tells us in English class, isn’t always recognised.

Anyway, you may be interested to hear that Phyllis is now behaving in an even more mysterious fashion. Yes, I thought the cabbage leaves and window-climbing was strange enough, but now she is receiving secret packages. Yesterday I was walking back from school when I noticed her walking ahead of me down Drumcondra Road with a strange woman in a dark green coat. It looked as if they were talking very intensely. And when they reached the corner of Clonliffe Road, the other woman passed Phyllis some sort of bundle. I couldn’t see what it was, only that it wasn’t very big, because Phyllis immediately shoved it into the bag she was carrying. Then the mysterious women crossed the road and went down Clonliffe Road and Phyllis kept going towards our house.

I caught up with Phyllis before she got there, and she nearly jumped out of her skin when I tapped her on the shoulder.

‘It’s only me,’ I said. ‘Who did you think it could be? A policeman?’

I hoped she might turn pale with guilt and reveal her dreadful secrets but she just looked annoyed.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ she said. ‘I just didn’t expect anyone to creep up behind me, that’s all.’

‘Where have you been?’ I said.

‘I’ve been with Kathleen,’ said Phyllis. ‘We went to a tearoom in town.’

‘I thought I saw you talking to someone back there,’ I said. ‘A strange woman in a green coat.’

And then Phyllis did turn pale. At least, a little paler than usual. But only for a second.

‘Oh, I bumped into a friend of Kathleen’s,’ she said. ‘She gave me a book she’d promised to lend her. She can’t visit because she doesn’t want to catch the flu. Kathleen’s sister’s come down with it now.’ Kathleen’s family do seem to be very susceptible to germs.

Anyway, I couldn’t prove this wasn’t true, because maybe the woman in the coat actually is a friend of Kathleen’s with a great fear of germs, and maybe that package was just a book – though it hadn’t looked particularly book-shaped – but I absolutely knew Phyllis was lying. I didn’t say anything, though.

I told Nora about all this at school today, and even though she has no imagination, she did admit it sounded quite suspicious.

‘Maybe she really is becoming a revolutionary,’ she said.

But I told her I didn’t think Phyllis had any political views at all. ‘She’s never said anything about that sort of thing,’ I said.

‘Not to you,’ said Nora. ‘But that doesn’t mean she hasn’t got any. She might think you wouldn’t understand. And she’d probably be right.’

I couldn’t help feeling slightly insulted that she thought I wasn’t the sort of sister someone could confide in about being a revolutionary.

‘It’s not like I’d tell Mother and Father,’ I said. ‘Well, I probably wouldn’t. Unless I thought she was going to do something dangerous.’

‘There you are, then,’ said Nora.

‘But we’re not a very political family,’ I said. ‘Not like your aunt. Mother and Father are just plain old Home Rulers.’

‘That doesn’t mean anything,’ said Nora. ‘People don’t always have the same political opinions as their parents. Otherwise nothing would ever change at all.’

You know that Nora can be a bit of a know-it-all, but I must admit that she had a very good point there. It still doesn’t mean that Phyllis really was up to any revolutionary activities. I will just have to keep an eye on her.

‘You mean spy,’ said Nora. Which sounded harsh, but I have to admit that there isn’t much of a difference between keeping an eye on Phyllis and spying on her. Though as I told Nora, ‘I’m not going to do anything really sneakish and dishonourable like reading her letters or anything. I’m just going to look out for any more mysterious behaviour.’ And that is what I will do.

You don’t suppose she could have fallen in with jewel thieves like Peter Fitzgerald, do you? It would explain the bundle. But that seems even more unlikely than her being a revolutionary.

Isn’t it awful about the Titanic? Julia read some of the newspaper reports and had nightmares afterwards. I must admit I kept thinking about it myself. Those poor people! We all prayed for them. Apparently a senior girl’s aunt was on the ship but they got a telegram and she is safe.

Well done on winning your hockey match. As my school is in the middle of the city (well, you can walk to Sackville Street from Eccles Street in about fifteen minutes) we don’t have as much space as you do out in the English countryside, but we do have a tennis court and a hockey team (there is talk among some of the older girls of starting a girl’s hurley team, which is sort of like hockey, but they haven’t actually done it yet). Luckily, we’re not forced to take part in hockey – as you know I do not enjoy that sort of thing. We are forced to take drill and dancing twice a week, however, and I am absolutely terrible at drill, which is basically just marching around doing stupid exercises, though even Nora admits that I am quite good at dancing. Maybe I could become a professional dancer when I leave school? It would be worth saying that’s what I want to do just to see the look on Aunt Josephine’s face ….

Do write soon,

Fond regards,

Mollie

P.S.

Mother is always telling me off for leaving letters in my writing case for ages before posting them, but for once my bad habit has turned out to be for the best because yesterday evening I made an exciting discovery and luckily I hadn’t put your letter in an envelope before I made it, so now I can add this post script and tell you all.

First of all, I knew that package Phyllis had wasn’t a book as soon as I saw it and I was right. At least, it wasn’t just a book. I think there might have been a book in there too. But anyway, what most of it was was pamphlets. And I know because I saw Phyllis giving them

to Maggie. I was slaving away in the dining room at my algebra and I was so caught up in x and y that my head started to hurt so I went to the kitchen to get a glass of water. The door to the kitchen was ajar, and as I went down the steps towards it I realised that Phyllis was in there talking to Maggie. And so, for the second time in just a few weeks, I stayed outside the door and peeked in.

Maggie was stirring something on the range, and Phyllis was leaning against the wall between the range and the big wooden dresser. And in her arms was a familiar bundle. The bundle that the strange woman had given her just a few hours earlier.

‘You shouldn’t have brought them down here,’ said Maggie. ‘I told you, we have to stop discussing these things in the house.’

‘Oh don’t worry, Maggie,’ said Phyllis. ‘Mother never notices anything.’ She paused. ‘Mollie did see Mrs. Duffy give me the parcel, though.’

Maggie turned round.

‘You’ve got to be more careful, Phyllis!’ she said. ‘If your mother finds out, I could lose my place and there’ll be no university for you. And you can say goodbye to the cause, too. You’ll be packed off to one of those aunts of yours and you won’t get near any sort of a meeting if they have anything to do with it.’

‘Mollie won’t say anything,’ said Phyllis. ‘She’s a good kid. She’s not a sneak. Besides, I told her the parcel was a book for Kathleen.’

I must admit I did feel rather sneakish and low when I heard that. There was Phyllis, praising me – she’s certainly never said anything so nice about me to my face – and there was me, spying at her through the door. And yet I couldn’t bring myself to leave.

‘It’s still too close,’ said Maggie. She sighed. ‘How do they look, anyway?’

Phyllis pulled back a corner of the bundle and took out what looked like some sort of leaflet.

‘See for yourself,’ she said.

Maggie’s back was to me as she took the leaflet and I couldn’t see what it said. But she seemed to like it.

‘Well, I must say they did a fine job,’ she said. ‘But like I said, we have to stop discussing these things in the house.’ She took the bundle and put it in a dresser drawer. ‘Anyone could walk in.’ And she turned towards the door. I immediately jumped back and then walked very loudly towards it, practically stamping with every step.

‘Hello!’ I said, pushing the door open. ‘Can I have a glass of water, please, Maggie?’

I was worried that my voice sounded a bit too cheerful, but both Maggie and Phyllis looked so rattled by my arrival I don’t think they noticed I was a bit nervous myself.

‘Of course you can,’ said Maggie, and she went into the scullery with a glass.

‘I’m going to my room,’ said Phyllis. ‘I have lots of letters to write.’ And without even saying goodbye to Maggie, she walked out of the room. I stayed in the kitchen for a while talking to Maggie and eating one of the delicious biscuits she’d made that morning, but all the time that Maggie was asking me questions about school and I was telling her about Grace Molyneaux and what a monstrous beast she’d been to me and Nora during drill and dancing that afternoon – telling Miss Noren that she was afraid we were talking instead of waving our arms about and how we were missing out on healthy exercise – all I could think of was the bundle of pamphlets just sitting there in the dresser drawer. And even though I knew it was sneaking and spying, I vowed that I would have a look at them later, after everyone had gone to bed.

Except I didn’t. I made a very special effort to stay up terribly late. I tried to think of lots of interesting and exciting things so I wouldn’t fall asleep, but I was so exhausted after all my earlier spying that my eyelids started to droop, and the next thing I knew it was seven in the morning. I knew Maggie would already be up, dusting the dining room and laying the fire, but I put on my dressing gown and slippers, and made my way as quietly as I could down through the house. When I reached the hall, I could hear the clang of the fire irons in the dining room so at least I knew Maggie would be occupied there for a few more minutes. And then I ran down the steps and into the kitchen.

But when I opened the dresser drawer to look at the pamphlets, they were gone! I should have known Maggie wouldn’t just leave them in a place where anyone could find them, not when she was so worried about having them in the house. She must have given them back to Phyllis, or hidden them away somewhere safer. And even I wasn’t going to be so low as to root around in her private things.

I closed the drawer and cut myself a slice of slightly stale bread and butter. I always think better when I’m eating something. Maggie had already made herself a pot of tea and it was still warm so I poured myself a cup and sat down at the kitchen table. I didn’t feel entirely happy about spying on Maggie and Phyllis, and as a matter of fact I still don’t, but now I’ve started investigating this mystery it really is very difficult to stop. Could I, I wondered, just drop the whole thing? Or could I just ask Phyllis or Maggie outright what is going on? But even if I did, I thought, chewing the bread and butter, they probably wouldn’t tell me. I was just thinking about this when the kitchen door opened and Maggie came in. She nearly dropped the dustpan she was holding when she saw me.

‘What on earth are you doing here?’ she said. ‘It’s usually hard enough to get you out of that bed in the morning.’

‘I couldn’t sleep,’ I said. Another lie. ‘You don’t mind me taking some of your tea, do you?’

‘Of course I don’t,’ said Maggie. ‘There’s plenty in the pot. But that’s yesterday’s bread.’

‘I don’t mind,’ I said.

‘Well, the baker will be along soon with a fresh loaf,’ she said. ‘And if you’ll excuse me, early bird, I’ve got to sweep the stairs now.’ And she headed out the door. I almost asked her about the pamphlets, but I didn’t dare. She’d know I’d been spying if I did, and I really did feel guilty about it. But I still do want to find out what it’s all about. It looks like Phyllis and Maggie really are revolutionaries after all. Why else would they have pamphlets?

I definitely am going to seal and post this letter now. I’ll write again as soon as something else happens. Surely I will find out the truth soon?

1st May, 1912.

Dear Frances,

Thanks awfully for your excellent letter. I like the sound of your new English mistress. She sounds much more fun than Professor Shields who teaches us English and French and who has eyes like a hawk and ears like a bat – I mean as powerful as a bat’s; they look perfectly normal. She’s about thirty and quite pretty really, but you can never get away with talking in class or passing notes. I must admit that apart from her magical observational powers, Professor Shields is all right. She’s not as bad as Sister Augustine, who taught us last year and has the most boring voice in the world. Though it’s quite hard to think about school at all at the moment, when I have found out the truth about Phyllis and Maggie. Yes, I know all (or at least, I think I do) and it really is quite shocking. It turns out they are revolutionaries – well, sort of. They are SUFFRAGETTES!

Yes! Actual suffragettes! At least Phyllis definitely is, and Maggie supports her. I can’t believe I didn’t think of it before (though neither did Nora, so it wasn’t just me being dim). But when I look back it all makes sense. Phyllis may not have seemed interested in politics, but she definitely has strong feelings about women being able to do things that men think they shouldn’t. Look at how she insisted on going to university. And she got that bicycle a few years ago even though Father Thomas (our uncle who is a priest) told Father that women on bicycles were a shocking disgrace and that the next thing we knew Phyllis would be wearing trousers and smoking a cigar (she has not done either yet, as far as I know, but who knows, maybe she will? It feels as though anything is possible now).

So in a way the news that Phyllis is a suffragette is not surprising. But still, I can’t help being a bit stunned by the whole thing. I mean, wanting to go to college doesn’t automatically mean you want the vote, and even want

ing a vote doesn’t automatically mean you’re actually going to go to meetings and chalk slogans on pavements and march around wearing a poster-board telling people about it and all those other things that suffragettes seem to do. Lots of people want something and never do anything about it. But Phyllis is definitely doing something about it, and Maggie is helping her. I can hardly take it all in.

Here’s how I found out. It was this afternoon – though it seems like much longer ago. We’d just had tea and I was in the dining room finishing my Latin exercises (Ovid this time, going on about his last night in Rome). Mother was in the drawing room, playing Mozart’s Rondo Alla Turca at top volume, which is always a sign that she is in a good mood; I could hear it rattling through the wooden doors that divide the drawing room from the dining room. Latin poetry is, as you know, terribly boring, so what with Ovid and the Mozart I couldn’t concentrate for more than a few minutes at a time and found myself staring out the window. Which is how I saw Phyllis carefully shutting the back door and making her way stealthily towards the back gate. And instantly I knew what I had to do. Ovid would just have to wait (he can wait forever as far as I’m concerned, though in this case I did have to finish it when I got home).

Now, Frances, you might think that what I did next was very sly and sneakish. And to be honest it probably was. I know I have been behaving in quite a sneakish way recently. But anyway, I did it. I leapt to my feet, ran into the hall, grabbed my coat (which I had left on the bottom of the stairs rather than hanging it on the rack) cried, ‘Mother, I’m going to borrow a school book from Nora,’ and, before she could say anything (or even let me know that she’d heard me), I raced out the back door (Maggie was washing up in the scullery, so I didn’t have to lie to her, too, about where I was going), through the back gate and ran down the lane. And while I may not be much good at drill and dancing, you might recall that I was always jolly good at races. And so Phyllis hadn’t even reached the end of our road by the time I emerged from the lane.

The Real Rebecca

The Real Rebecca Once

Once Rebecca Rocks

Rebecca Rocks Blackbird

Blackbird Rise

Rise Rebecca's Rules

Rebecca's Rules Deadfall

Deadfall Eve

Eve The Making of Mollie

The Making of Mollie Sloane Sisters

Sloane Sisters Survival of the Fiercest

Survival of the Fiercest This Is Not the Jess Show

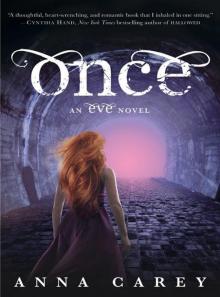

This Is Not the Jess Show Once: An Eve Novel

Once: An Eve Novel