- Home

- Anna Carey

The Boldness of Betty Page 5

The Boldness of Betty Read online

Page 5

After that day Mr Casey stopped going to Mass and he still doesn’t go, which shocks a lot of people around here because everyone on our road goes to Mass, apart from the Marshalls, who are the only Protestants in Strandville Avenue. And even they go to their own church at the corner of Waterloo Avenue. But Mr Casey didn’t care what other people thought. He said he wasn’t going to say any prayers with the men who tried to take his children away.

In fact, he almost didn’t even have Samira christened, but his ma, Samira’s grandma, insisted on it. She lives across the river in Ringsend and she organised it all in her local church so Mr Casey didn’t have to do a thing. But even with old Mrs Casey sorting it all out, her parish priest refused to christen the baby Samira – which was the name her ma had chosen before she died – because it’s not a saint’s name. I think Samira is a lovely name and I’d much prefer to be the only person around here with my name, which certainly isn’t the case with Betty. There were two other Bettys in our year at school and four more Elizabeths. There’s even another Betty at Lawlor’s but she works in the sink room so I don’t have much to do with her.

Anyway, even though Auntie Maisie argued with the priest about it, he wouldn’t give in, so in the end Samira ended up being christened Sarah, which is in the Bible and which I suppose sounds a little bit like Samira. But although Sarah is on her baptismal certificate, everyone around here has always called her Samira, apart from some of the teachers and nuns at school who insisted on calling her Sarah. And as for Ali? All the Christian Brothers in Joey’s, the boys’ school where he went until he left and got a job two years ago, called him Alan.

Ali’s not bad as far as big brothers go. He’s quite serious a lot of the time, but he has a sense of fun too, and he’s certainly less annoying than our Eddie. Ali and Samira get on well most of the time. They tease each other a lot, but it’s never nasty. Maybe it’s because of not having a ma and the two of them being the only kids in our area who weren’t as pale as skimmed milk. As their friends we stuck up for them when anyone said something horrible, but we couldn’t really understand what it was like to have those things said to us.

Because Ali and Samira get on so well, the three of us sometimes sit around the fireplace in the Caseys’ front room (which turns into Ali’s room at night), talking away. Sometimes Ali’s pal Tom McGowan calls over too. Auntie Maisie comes in every so often to keep an eye on us and make sure we’re not actually lighting the fire. (There’s never enough coal to have a fire in the front room and the kitchen, so the front room fireplace is only lit when the whole family are in there.) Ali always has funny stories about work, but he doesn’t just hold forth and expect us to sit there in silence listening to him like some boys I could mention (Eddie). He actually listens to what me and Samira have to say.

So now you know all about Samira and her family, I can continue my tale of today’s events. Like I said, I called into McGrath’s to say hello to Samira on my way to work, and when I walked into the shop she was leaning on the counter, gazing dreamily into the distance.

‘Morning!’ I said, and she jumped up with a guilty air, until she realised it was just me, and not a paying customer who might tell Mrs McGrath she was daydreaming instead of doing some productive work.

‘You looked like you were away with the fairies,’ I said. ‘Where’s Mrs McGrath?’

‘She’s got one of her heads,’ said Samira. ‘And I was just being Lady Macbeth.’

From some people that might have sounded a bit worrying, but I knew Samira was just acting out a Shakespeare play in her head. That’s another good thing about me and Samira being friends. We’re never ashamed to tell the other about the things we imagine, even though we know loads of people would think we were daft.

‘Isn’t she the one who persuades her husband to kill people?’ I said.

Samira nodded. ‘The very same. What do you think the odds are of a famous Shakespeare producer’s car breaking down on his way to Clontarf or somewhere, and coming in and asking me to be in his new show?’

‘Fairly low, I should think,’ I said. ‘But if one does, ask him to give me a job too. One that doesn’t mean standing up all day.’

‘What would you do in a theatre?’ said Samira.

‘Prompter,’ I said. ‘Whenever you forgot your lines I’d remind you.’

‘I’d never need reminding,’ said Samira indignantly.

‘Howiya, girls?’ Ali was standing in the doorway. ‘Quarter pound of bullseyes please, Sam.’

‘Look at you, Mr Money-bags,’ I said, as Samira scooped out some sweets and put them on the scales.

‘It’s for Tom,’ said Ali, handing over a few pennies to his sister. ‘He’s leaving today so we promised him we’d have a goodbye party in the storeroom.’

‘He didn’t get the sack, did he?’ I hoped he hadn’t. We all like Tom, who lives in East Wall and works with Ali in a big newspaper delivery room, sorting out the papers before they go to the shops and the street sellers. Jobs are hard to find these days, so if he got sacked from the delivery room he might find it hard to get another decent job.

‘Saint Tom? Not he,’ said Ali. ‘He got a better job on the trams.’ He grinned at Samira. ‘Poor Samira’s brokenhearted. He won’t be coming back to our house after work so often.’

‘Be quiet, you,’ said Samira crossly. She does actually like Ali’s friend Tom – like I said, we all do – but she hates me and Ali joking about the pair of them. Which I’m afraid to say I often do, ever since the Sunday a few weeks ago when Tom’s cap fell out of his back pocket as he was leaving their house and Samira ran up the road after him shouting ‘Tom! Tom!’ in a sort of Romeo and Juliet voice. At least, that’s how I described it to her, but she got very annoyed and said it was just her usual voice.

But while I don’t mind teasing Samira when it’s just the two of us, I’m not going to side with Ali against her, even in jest, so I looked at him as disapprovingly as I could and said, ‘Leave your sister alone.’

My disapproving look must have been quite successful, because Ali laughed and said, ‘All right, Queen Victoria. Sorry, Sammy. Pax?’

‘Hmmph!’ Samira tossed her head in a very dramatic and haughty fashion but she can never stay angry at Ali for long. ‘Oh, all right, pax.’

‘I’ll give Tom your love,’ said Ali, and before Samira could throw a jar of Bovril at him he dodged out of the shop.

‘I’d better go too,’ I said. ‘Don’t mind him.’

‘I never do,’ said Samira, raising her eyes to heaven, and then Mrs Hennessy came in looking for Mr Hennessy’s tobacco so Samira had to serve her. To my surprise, when I came out Ali was leaning against the railings of the house next to the shop, waiting for me.

‘I thought you’d have gone on,’ I said.

‘Eh, we might as well walk in together,’ said Ali. ‘If your majesty doesn’t mind, of course.’

‘’Course not,’ I said, because I didn’t. We strolled towards town in a companionable silence. That’s another thing I like about Ali. I never feel awkward around him, not like when Eddie’s friends call around to our house. Maybe that’s because unlike Eddie and his pals, Ali never makes me feel like a freak of nature for reading books and caring about things. As we crossed Newcomen Bridge, I found myself glancing down the canal towards the library and, beyond it, my old school. It seemed like forever since Samira and I were going there every day.

‘Missing the old school?’ It was like Ali could read my mind.

‘Sort of,’ I said. I gestured back the way we’d come, towards Joey’s. ‘Do you miss yours?’

‘I can’t say I miss being walloped with a belt.’ His voice was light but when I looked at him he didn’t look like he was joking.

‘They never used a belt in our school,’ I said. ‘Just the cane.’

‘Oh, that’s all right then.’ Ali couldn’t hide the sarcasm.

‘But I suppose it’s just what they do in schools, isn’t it? It’s not like you can change it.’ I shrugged my shoulders, even though I’ve always thought that it was wrong that teachers are allowed to hit children whenever they feel like it. Luckily we had Miss Hackett for the last few years, and she didn’t seem to like beating anyone. There was only the odd rap on the hand with a ruler for children who were really acting the jinnet.

But I knew we were very lucky to have her as our teacher. There were other teachers in the school who didn’t mind giving you a proper wallop when they felt like it. And I remembered that when Ali had been there in the junior school, some of the teachers had been fierce hard on him.

‘I don’t see why it can’t be changed,’ said Ali. His face was more serious than I’d ever seen it before. ‘If I’d been able to train as a teacher, I’d reef the belt out of the hands of any Brother I saw belting a kid.’

I looked at Ali in surprise. ‘Did you ever want to be a teacher?’

Now it was Ali’s turn to shrug his shoulders. ‘I dunno. I thought about it.’

We had passed the canal now, and were almost at the Five Lamps. ‘You kept that very quiet,’ I said.

‘What’s the point of mentioning it?’ He let out a laugh that didn’t have much humour in it. ‘It’s not like it was ever going to happen.’

‘Well, I don’t know if Samira’s ever going to play Lady Macbeth in front of the kings and queens of Europe,’ I said. ‘But that doesn’t stop her going on about it all the time.’

Ali laughed – a proper laugh this time, I was relieved to note.

‘True enough,’ he said.

‘And you never know,’ I said, warming to my theme, ‘maybe Samira really will become a famous actress and she’ll be so rich she’ll be able to pay for you to go back to school and become the best teacher Dublin has ever se

en.’

‘I’ll believe that when I see it,’ said Ali with a grin. And things were fine again. But I don’t think I’d ever seen Ali look as grim as he did when he was talking about being beaten by those nasty old Brothers.

After that we mostly just talked about ordinary things, like how much we want to go to the new picture palace in Capel Street, and how many midnight union meetings our das have been going to recently. I know the union is important, because all the workers are trying to stick together, but I don’t know how they manage to go to all those meetings. I’ve never been able to stay up until midnight. I start falling asleep at around half past nine, and it’s even worse now I’m working all day. I’m practically sleepwalking home from Lawlor’s.

Anyway, when we reached the crossroads just before the railway bridge at Amiens Street Station, Ali veered right to go down Foley Street.

‘Where are you going?’ I said, stopping short.

‘It’s the short cut,’ said Ali. ‘You can skip the corner and get halfway down Talbot Street.’

‘I know, but …’ I looked at the ground. ‘Ma doesn’t let me go that way.’

Foley Street and the streets around it have a bad reputation for being what Ma calls ‘very rough’. They call the area Monto, because Foley Street used to be called Montgomery Street until a few years ago.

Ali shrugged his shoulders. ‘Well, if you don’t want to walk that way, then I won’t make you.’

I drew myself up to my full height (which still isn’t very tall). I didn’t want to look like a baby in front of Ali. ‘No, it’s all right. You’re right, it would be a lot quicker.’

‘Only if you’re sure,’ said Ali.

‘Come on,’ I said. And I marched down the street ahead of him.

I don’t know exactly what I expected Foley Street to look like. I thought there’d be, you know, people lying around drunk in the street or fighting and that sort of thing. But it was pretty quiet that morning. There were the usual shabby old houses that had seen better days, with young women sitting outside their open doors watching us with wary eyes. There were children playing in the street too. None of them had shoes on and some of them had the tell-tale close-cropped heads that showed they’d had nits and had to have their hair shaved off.

‘They’re out early,’ I said.

‘Sure there wouldn’t be enough room for them at home once the whole family was up.’ Ali’s tone was dry. Sometimes I forget how lucky we are. Around Foley Street whole large families are crammed into single rooms in the tenement houses, with seventy people sharing a single toilet outside. I suppose to them our house, with its very own jacks and four whole rooms, would seem like a mansion.

As we walked down Foley Street I saw a skinny kid with closely cut red hair trotting towards the door of one of the tenements carrying a battered old saucepan full of burned-out cinders. You see boys and girls doing this a lot near the tenements. I knew he must have gathered them from the ash bins of rich families across the river, and he was taking them home so his ma could use them to make a fire to cook whatever food they had. I shivered despite the warmth of the day. The kid was wearing what looked like the contents of a rag bag – a lady’s coat that was much too big for him, a ragged man’s shirt and a pair of shorts that looked like they were about to fall to pieces. His grubby feet were bare. There was something familiar about him.

‘Poor little thing,’ I said to Ali, nodding towards the boy with the cinders, who had spilled some of his load and was scrabbling at the foot of the steps to gather up fragments of coal. As he threw the last piece back into his pot, a red-haired girl in a faded blouse and skirt stuck her head out of the front door of the house. She said something to the boy and started to take the pot off him, but then she saw me and Ali. And she froze.

That was when I recognised her, and with a wave of shock I realised why the boy was familiar. The girl’s name was Margaret Maguire and the boy was her little brother Tony. They used to live on our road – their da used to get casual work on the docks. Da works full time for the Dublin Port and Docks Board, and so does Samira’s da, so they’ve got a steady wage coming in every week, but other men just go to a pub every day and hope the stevedore chooses them to work on the docks that day. If he doesn’t choose them, they have no work. And no pay.

But Margaret’s da got work regularly enough, and they were doing alright for a long time. They lived in a house the same size as ours. It must have been a squeeze because Margaret was the second oldest of five kids, but that’s just the way it often is on our road. Me and Samira always liked Margaret. She was a year older than us but she didn’t look down on us and treat us like kids, like some of the older girls (including Lily).

But then one day a crate fell on Mr Maguire’s arm when he was loading it onto a lorry. All the bones in his arm were crushed, and after that he couldn’t work anymore. Margaret and her older brother went out to work and their ma pawned her wedding ring, but that wasn’t enough to feed the family and pay the rent for very long. It must be about six months ago when the rent man came to collect that week’s payment and discovered the whole family had done a moonlight flit in the night. They’d run away under cover of darkness. No one had seen them go and no one knew where they went – or at least if they did, they weren’t telling. And as far as I knew, no one from Strandville Avenue had seen any of the Maguires again – until now.

‘Haven’t seen you in a while, Margaret,’ said Ali easily. If he was as shocked as I was to see that Margaret was living in one of the roughest streets in Dublin, with her brother spending his mornings going through other people’s ash bins for fuel, he didn’t show it. ‘How are things?’

‘Ah, you know, Ali,’ said Margaret. She swallowed, as if her throat was dry. ‘Not bad. How are you, Betty?’

‘Grand,’ I said. ‘It’s good to see you. Are you …’ I suddenly felt as if I shouldn’t even ask. ‘Um, are you living here now?’

Margaret looked down at the ground. Her hands were red and cracked from hard work. The blouse that must have been white once was now a sort of grey. Her boots were battered and far too big for her. I realised they were men’s boots. They must have been all she was able to find at one of the second-hand clothes markets.

‘We are.’ She glanced back at the house she’d come out of. I followed her gaze and noticed lots of the windows had broken panes. Bits of tatty cardboard had been used to patch the holes. I can’t imagine they were much good when it rained.

‘How’s that big brother of yours?’ said Ali, his tone still cheerful. ‘Still at that night watchman job at the warehouse?’

Margaret flushed. ‘He’s not working at the moment. He got let go.’

Ali’s voice was sympathetic. ‘It’s happening a lot these days,’ he said.

‘What are you up to yourself?’ I asked. Suddenly I was very conscious of my neat Lawlor’s frock. My boots, which had seemed so large and clumsy in the Lawlors’ house, looked like dainty slippers in comparison to Margaret’s. ‘I mean, where are you working?’

‘I’m charring for a family on the North Circular,’ said Margaret. ‘Just doing the rough work in the house, you know.’ She laughed, but it sounded more like a cough. ‘All the things their maid won’t do.’

‘Well, I hope they’re paying you enough for it,’ said Ali. ‘And speaking of work, we’d better make haste, Betty.’

‘Don’t let me keep you,’ said Margaret. She didn’t say it rudely. She just sounded sad.

‘See ya, Margaret,’ I said. It felt strangely inadequate.

‘See ya,’ said Margaret. There was a dullness about her that hadn’t been there before her da’s accident. She went back into the house, and Ali and I kept going.

‘Janey,’ I said. ‘So that’s where they went.’

‘It doesn’t take much to end up there,’ said Ali. ‘One broken arm, that’s all it took the Maguires.’

I have to admit that the idea shook me, how close we all could be to living squashed into one tiny room. I know Ma’s always tried to protect us from that world. She’s always wanted to be respectable. ‘We may not have much money,’ she’ll say, ‘but we’ll never go hungry and we’ll always go shod.’ And she’d rather we didn’t have anything to do with the people who were hungry and didn’t have shoes.

The Real Rebecca

The Real Rebecca Once

Once Rebecca Rocks

Rebecca Rocks Blackbird

Blackbird Rise

Rise Rebecca's Rules

Rebecca's Rules Deadfall

Deadfall Eve

Eve The Making of Mollie

The Making of Mollie Sloane Sisters

Sloane Sisters Survival of the Fiercest

Survival of the Fiercest This Is Not the Jess Show

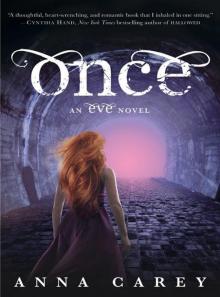

This Is Not the Jess Show Once: An Eve Novel

Once: An Eve Novel