- Home

- Anna Carey

The Boldness of Betty Page 7

The Boldness of Betty Read online

Page 7

‘You don’t have time to go all the way out there anyway,’ said Ma. ‘You’ve got to be back for your dinner by two.’

Then Lily piped up with a maddening suggestion. ‘Why don’t you go out there after dinner so he can have a little paddle? It’s gorgeous weather today.’ She looked fondly at Little Robbie, who was crawling around the kitchen floor with a big red face on him. He’s got loads of teeth coming in at the moment so he’s even redder and more angry than usual. Those pointy teeth poking through your gums must be pretty sore; I suppose I’d feel sorry for him if he wasn’t so awful. But he is.

‘I’m not taking him for a paddle!’ I couldn’t believe they were all wrecking my day off like this. Then a thought struck me. ‘It’s supposed to be the day of rest,’ I said, in what I hoped was a holy sort of voice.

‘Go away out of that, you!’ said Da with a grin. ‘Babies have to be looked after, even on Sundays.’

‘Not by me they don’t,’ I said, but I knew I’d lost the battle with all of them ganged up against me. I hope in the future, when I am a famous author, people will appreciate the terrible hardships I had to go through. This is another reason why I’m writing this memoir, to document my woes for posterity.

Samira wasn’t as horrified as I thought she’d be when I turned up at her door with Little Robbie in his pram. (It’s massive, but Ma got it in a pawn shop on Capel Street for a very decent price.) This is because Little Robbie actually likes her. As soon as he saw her, his angry red face broke into a beaming smile. A smile which looks just as horrible as his scowl, if you ask me, but no one else seems to think so.

‘Samma!’ he said and he reached out his chubby little arms towards her.

‘Aww, hello there, Little Robbie!’ Samira beamed back at him. ‘Thou wast the prettiest babe that e’er I nursed.’

‘He isn’t pretty at all,’ I said. ‘And you never actually nursed him.’

‘Don’t argue with Shakespeare,’ said Samira. ‘That’s from Romeo and Juliet.’ She picked up Little Robbie to give him a hug, like the traitor she apparently is. ‘Aren’t you a happy boy today?’

Little Robbie chuckled.

‘He wasn’t happy two minutes ago,’ I said grumpily. ‘I tried to put his gansey on and he went all stiff like he was made of wood and wouldn’t bend his arms.’

‘Don’t mind your nasty Auntie Betty,’ said Samira, still smiling at Little Robbie and bouncing him about in her arms. ‘Is that a new little toothy? Yes it is!’ And she tickled him under his chin and made him laugh and laugh.

‘He never does that for me,’ I said.

‘Didn’t your auntie say that making babies cry runs in the family?’ said Samira, as Little Robbie gleefully grabbed her finger and started chewing it.

‘It does,’ I said. ‘But in this case I think Little Robbie just knows what I think of him.’ When I was giving out about Little Robbie over the Christmas, Auntie Eileen said that some Rafferty women seem to have a terrible effect on other people’s babies. ‘I couldn’t walk past a baby without it bursting into tears,’ she said.

‘But what about Frankie and Joe?’ I said. They’re her kids, which of course makes them my cousins.

‘Ah, they liked me well enough,’ she said.

Anyway, I don’t care why Little Robbie hates me, I just care that I had to take him out when we went on our nice Sunday walk. Strangely enough, Samira didn’t seem to mind.

‘Sure, we can’t stay out too long anyway,’ she said. ‘We’ll have to get back for dinner. He’ll be asleep for most of it.’

And so we walked up our road with Little Robbie hooting away. Actually, before my memoirs go any further, I suppose I should describe the road where we all live. It’s called Strandville Avenue and it’s in the North Strand, which is a very good place to live because town is a mile away in one direction and the sea is less than a mile away in the other direction.

There are not one, not two, but three railway lines along our avenue. Two of them go right over the road on big railway bridges. Then at the very bottom of the road there’s the high railway embankment, and trains go along that line all the time, all the trains for Malahide and Howth and Skerries and even Belfast.

Ma hates living near so many trains, she says the smoke from the engines makes her washing all dirty when it’s out on the line, but I love having all the train lines here, even though I know she’s right about the smoke. When I’m asleep I can hear the freight trains passing in the night, and sometimes I imagine they’re those fancy trains you read about in books, with sleeping compartments and everything, and I imagine that instead of being tucked up in bed (with Lil, in the old days, which gave me a good reason to imagine being somewhere different), I’m all cosy and warm in a sleeping train, travelling somewhere exciting and glamorous like Paris or Vienna or even Istanbul.

I said this to Lily one night, back when I still had to try to go to sleep with her horrible hooves in my face, and she said, ‘What are you talking about? The furthest you’ve ever been from the North Strand is Skerries.’ She has no imagination at all.

As we turned towards the coast road I told Samira that if she was so happy with Little Robbie coming along she could push his giant heavy pram.

‘That’s grand,’ she said. She looked almost as cheerful as Little Robbie himself, who kept saying ‘Samma, Samma!’ and laughing and expecting Samira to sing songs to him. Which she did, the fool. But I suppose she thinks it’s all practice for when she goes on the stage. She’s a very dramatic singer. Once she flung her arm out when singing ‘I Dwelt I Dreamt In Marble Halls’ and knocked Auntie Maisie’s favourite vase off the front room mantelpiece.

Anyway, today she wasn’t too dramatic but she sounded very happy when she sang, much more cheerful than I’d be if I was pushing Little Robbie around.

‘What are you so jolly about?’ I said, laughing.

‘I have news,’ she said, giving a little skip. ‘Auntie Maisie says she’s going to take me to see Romeo and Juliet at the Majestic next week. Do you think you’ll be able to come too?’

‘I doubt it,’ I said. ‘But I’ll see.’

‘You can tell your ma and da it’s educational,’ said Samira. ‘And Auntie Maisie will be with us. It’s not like we’re running off to see some dancing girls.’

‘It’s not that.’ I sighed as I helped Samira get Little Robbie’s pram up the kerb. ‘We can’t spare the money at the moment.’

‘Even Auntie Maisie-rates?’ said Samira.

Auntie Maisie gets in free to all the theatres because of her old pals. She doesn’t perform on the stage anymore, but she knows everyone in all the theatres and music halls in Dublin. They let her and Samira in for free to all the shows and give them the cheap seats up in the gods.

These doormen are doing Maisie a big favour, and they can’t really give her more than two free tickets at a time, but sometimes, if she asks well in advance, they’ll give her an extra half-price seat. That’s how I’ve been to the theatre with them. I’ve gone a fair few times. We went to see a very good play called The Colleen Bawn last year which was very exciting and which we all liked a lot. There was a bit where a girl fell off a cliff into a lake and you’d think it was real water, it was so dramatic. But much as I’d like to go to the theatre now, it didn’t seem affordable.

‘You know some of the bosses are coming down hard on strikers at the moment,’ I said. ‘I heard Ma tell Da that if he doesn’t watch out he won’t have a job.’

‘But our das aren’t day labourers,’ said Samira. Everyone round here wants to be permanent like Da and Mr Casey, because at least you know that you’re definitely going to earn a steady wage every week. But as my ma and da keep reminding me, no job is safe these days. And if Samira hadn’t been so distracted this afternoon by her dreams of a trip to the theatre, she’d have remembered that.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I said. ‘I heard him and Ma talking. Things are getting very hot down there. They could sack everyone.’

‘Maybe just ask your parents anyway,’ said Samira hopefully. ‘You never know, Maisie might be able to get a ticket for nothing at all. Tommy Garland’s doing the door at the Majestic these days and I swear he’s sweet on her. At her age!’ She looked horrified at the thought of anyone fancying her aunt. ‘She’s almost forty.’

‘She looks younger than that, though,’ I said, and it’s true, she does. Back in the days before she gave up her life on the music halls to look after Ali and Samira she must have been a raving beauty, and she’s still the best-looking woman on our road now, however old she is. Ma says Auntie Maisie wears too many feathers in her hats, but I know she likes her really. It’s impossible not to. And whenever Maisie decides to have a new frock (which isn’t often – no one on our road can afford new frocks, but Maisie sometimes gets old costumes from the theatres that can be turned into something new), she gets Ma to do it for her.

‘No one can turn out a skirt as well as you, Mrs Rafferty,’ she’ll say. ‘You’re a genius!’ And I swear Ma simpers at the flattery. Maisie’s such a charmer, as I said to Samira.

‘There you go,’ said Samira. ‘Maybe she’ll charm Mr Garland into getting a free ticket for you. Oh, I hope you can come too. It won’t be the same going to see the play without you, not after us practising it together.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘Janey, it feels like ages since we were acting out those scenes.’

It was last year that Samira discovered Shakespeare and decided she was going to be a serious actress. Before that she’d always talked about going on the halls like Maisie – doing a few songs and comic turns, you know, little sketches and dances, and that sort of thing. Maisie was never a big star but she did well enough in the music halls and in pantomimes.

‘And I never had to rely on some aul’ fella to keep me either,’ she said one day when we were looking through some of her old theatre programmes. I wasn’t sure what she meant by that, and she didn’t get a chance to tell me because Mrs Casey, Samira’s granny, sat up straight in her chair by the fire where we all thought she was fast asleep and said, ‘We’ll have none of that sort of talk in front of the childer!’ So Maisie didn’t tell us anything else about aul’ fellas.

Anyway, like I said, Samira always wanted to follow in Auntie Maisie’s footsteps, and I bet she still could if she wanted to. But last year, in English class, our teacher Miss Hackett read a bit of this speech from a Shakespeare play called The Merchant of Venice. Some girl called Portia is pretending to be a lawyer and she gives this big speech in court. (At least I think it was in a courtroom – I never read the entire play so I was never very sure of the details.) The rest of the class didn’t care much about it, but I had to admit there was something kind of magical about the words, even though I couldn’t understand most of it.

And if I was mildly interested in the speech, Samira was completely entranced. After school that day she insisted we go straight across to the library to find a copy of the play.

‘They’ll have to have it there,’ she said, and she was right, they did. It was a little red book and it was in the grown-up section, but the librarian, Miss Hamilton, lets us get out books for grown-ups because we’ve read everything in the children’s room by now. Samira took it home and read it and by the following week she’d learned that whole speech off by heart.

And believe it or believe it not, she was actually pretty good when she recited it. No offence meant to Miss Hackett, who wasn’t bad at reading the speech, but Samira was much better. She made it sound like something a real person would say, not just a sort of poem. After that, she went Shakespeare-mad. She got all the plays out of the library, even the really confusing ones, and she learned loads of the speeches of the girls’ parts.

But of course, there’s only so much acting you can do on your own, and it wasn’t long before Samira started nagging me into playing some of the other characters. That’s how we ended up doing Romeo and Juliet together. She stood at my bedroom window and cried, ‘Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?’ while I stood in the back garden below and pretended to climb up the drain pipe to get to her, which was good fun until Eddie came home and saw us and laughed so much I thought he was going to be sick.

I really would like to see Romeo and Juliet performed by proper actors (and without fools like Eddie standing around sniggering), but I was almost sure that Ma and Da would think it’s too much money at the moment. Or at least Ma would. She thinks striking all the time is making the employers even more angry. But Da is sure that if all the workers hold their nerve and refuse to give in, they won’t have to fear the bosses for much longer. I think he’s right. It’s not as if they’re stopping work just for fun. They’re doing it to make things fair.

Oh no, I’ve done it again. I’ve got distracted from what actually happened today and started going on about Auntie Maisie and our Shakespearean readings and strikes. So I will return to this afternoon.

We kept walking towards the sea. When we set off I had a horrible feeling that Little Robbie was going to spend the entire walk wide awake, demanding Samira’s adoration and devotion, and I was even more afraid that she was going to give it to him, but to my great relief (and surprise, if I’m being honest) his eyes started to close soon after we left our house. I suppose Lily was right. He really was due his afternoon nap.

We paused for a moment after we crossed the bridge into Fairview and looked at the Tolka river spilling out towards Dublin Bay. You can see all the cranes from the docks where both our das work. As you look north towards Howth everything seems to stretch out, and soon you feel as if the city is falling away behind you and all that’s ahead of you is wild waves all the way to Wales. Sometimes it smells terrible, especially when the tide is out and all you can see is mud and bits of old rubbish that people have chucked into the water, but I still love living near the sea. Rosie’s ma comes from Athlone or some such place and Rosie says she’d never seen the sea until she came up to Dublin to go into service in a house in Sutton. I can’t imagine what that must be like. It’s like never having seen the sky.

I said that to Samira as we walked past the vitriol works (I’m glad Da and Eddie don’t work there, they’d come home stinking) and she agreed.

‘Especially in the summer, when everything is blue,’ she said, gazing out across the bay. ‘It’s like you’re right out there in the sky and the water. “Perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn!”’

‘Is that more Shakespeare?’ I said.

‘Keats,’ said Samira. ‘Anyway, perilous or not, it’s very good for calming the nerves.’

‘I suppose it’s not very calming in winter,’ I said, thinking of the days when the wind blows straight across the sea and you have to lean forward to be able to walk at all. ‘It’s hard to imagine winter now, isn’t it?’ I looked out at the blue sky and the barely moving waves as I kicked a stone along the dusty pavement.

We continued walking along Fairview, and as we passed the turn for Philipsburgh Avenue I said, ‘Has your da heard anything new about the union recreation ground they’re talking of setting up down there in Croydon House? You know, the big old house with the huge gardens? Da says they’re going to have all sorts of activities for the workers and their families.’

Samira knew all about it.

‘They’re going to have a big garden party for the workers soon,’ said Samira. ‘There’ll be games and teas and all that sort of thing.’

‘That union house reminds me,’ I said. ‘You know Rosie at work?’

‘Well, I know who she is,’ said Samira, and I don’t think I was imagining that she said it a bit cagily. It felt a bit strange, talking about Rosie to Samira. Samira spends her work days with old Mrs McGrath, which is grand because she’s a nice enough old bird, but they’re not exactly pals. Not least because Mrs McGrath is about a hundred years old. (Oh all right, she’s about sixty.) And she talks about nothing but her lumbago and how she can’t reach the tobacco shelf anymore, and she has no interest in Jane Eyre or singing or acting or all the other things Samira is interested in.

Whereas, even though it’s only been a few weeks since I started at Lawlor’s, me and Rosie have become proper friends, and I suppose I do talk about her to Samira a bit. Which might be quite annoying if you were stuck with an old lady all day. Sometimes I remember how jealous I was when Samira and Lizzie French became friends when we were ten. (Lizzie moved to Ringsend after that summer and we haven’t seen her since.) Then I feel guilty about going on about Rosie.

‘She’s joined the union,’ I said.

‘Has she?’ said Samira carelessly. She really is a good actor, but this time the carelessness was slightly overdone.

‘I didn’t think girls could join it at all,’ I said. ‘But they can.’

Samira looked right at me (luckily the pavement was empty so there was no danger of her pushing Little Robbie’s pram into anyone).

‘Are you going to join?’ she said.

‘I might,’ I said. ‘And you could join too.’

Samira snorted.

‘Why not?’ I said.

‘I work in a shop, in case you’ve forgotten!’ said Samira. ‘And you’re in a teashop. We’re not exactly hauling sacks down the docks.’

‘But you’re still a worker!’ I said. ‘We both are!’

‘I suppose,’ said Samira, but she didn’t sound convinced. I’m not entirely convinced myself, to be honest. I can’t really imagine ordinary girls ever going on strike like the men. But I do like the idea of us all joining together, and I said so to Samira.

‘We might be able to change things,’ I said. ‘Do you think things are fair right now?’

‘Of course not,’ said Samira. ‘But what can a lot of girls do to change that?’

And I didn’t have an answer to that.

Little Robbie was still asleep when we reached the crescent at the end of the Malahide Road. Although it’s a terrace like our road, the houses are about five times the size of ours. And there’s a lovely little moon-shaped park in front of it that belongs to the owners. We wheeled the pram to the railings and peered into the park, where we could see some children running across the grass playing a game of chasing. An older woman, who was dressed so plainly I knew she must be a servant, was sitting on a tree nearby, watching them. The grass looked so fresh and cool after our walk along the dusty hot streets.

The Real Rebecca

The Real Rebecca Once

Once Rebecca Rocks

Rebecca Rocks Blackbird

Blackbird Rise

Rise Rebecca's Rules

Rebecca's Rules Deadfall

Deadfall Eve

Eve The Making of Mollie

The Making of Mollie Sloane Sisters

Sloane Sisters Survival of the Fiercest

Survival of the Fiercest This Is Not the Jess Show

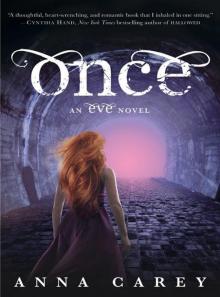

This Is Not the Jess Show Once: An Eve Novel

Once: An Eve Novel